When Language Loses Precision, Training Loses Direction

When Language Loses Precision, Training Loses Direction

The fitness industry does not suffer from a lack of information. It suffers from language used outside its proper context.

It’s funny how clear this is when the context is obvious: Weightlifting is about identifying the most powerful athlete. Powerlifting is about identifying who can lift the most weight.

Problems arise when words are stripped of context but still treated as if they carry a single, universal meaning.

We routinely use the same words to describe different physiological phenomena, then argue as if we are debating the same thing. We are not. As a result, productive conversations turn into semantic stalemates, and flawed training ideas persist not because they work, but because they are poorly defined.

“Intensity” is a familiar example. In exercise physiology, intensity refers to effort relative to maximal capacity. In resistance training, this is typically expressed as a percentage of one-repetition maximum. By that definition, an 85 percent back squat is high intensity, while a 30 percent kettlebell circuit is low intensity. Yet that same kettlebell circuit may feel metabolically brutal and be labeled “high intensity” in a conditioning context. Both uses are internally consistent, but they describe entirely different stressors.

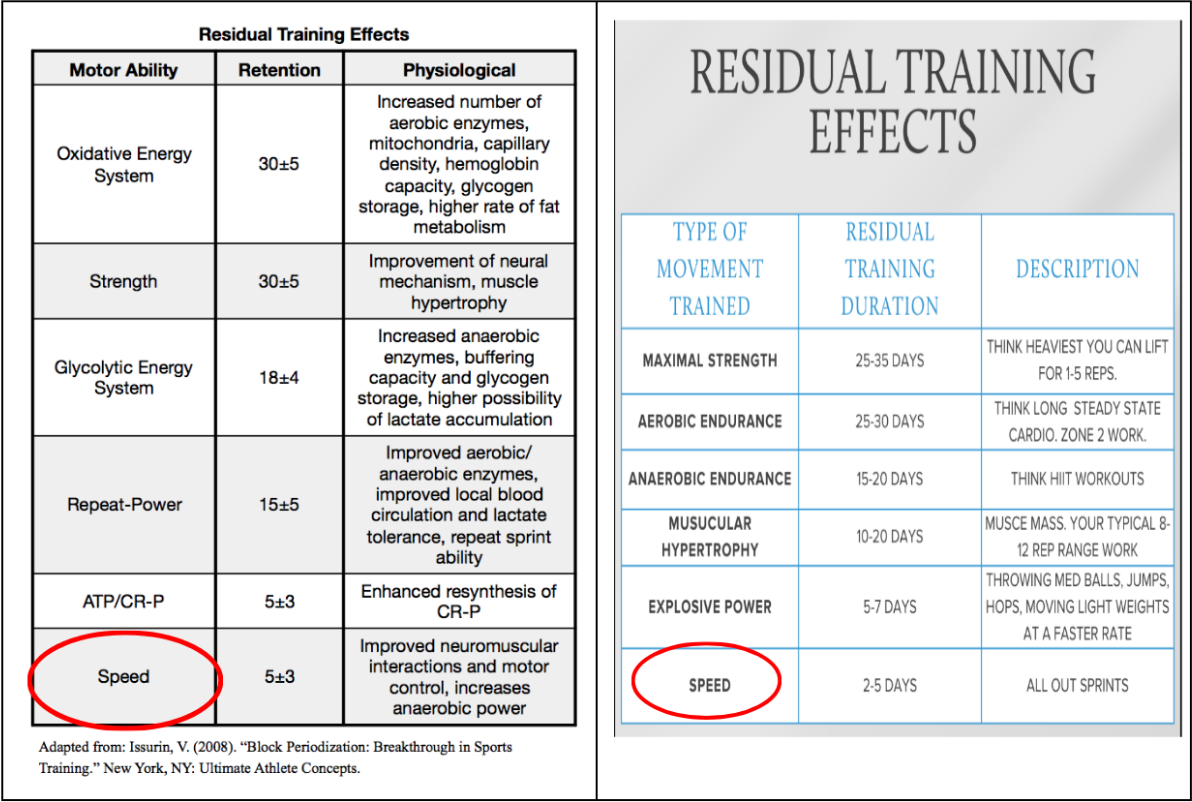

The same issue exists with “speed.” Sometimes it refers to sprint velocity. Other times it refers to the rate of force development. These are not interchangeable qualities, yet they are often discussed as if they were. Think about it, which one of those meanings is the ever so popular residual training effects chart (see image below) referring to? Confusion only appears when speed is discussed without context, and people start debating training methods as if they were targeting the same quality when they are not. This is exactly how coaches end up arguing past each other.

These aren’t rookie mistakes. They’re context failures.

When context fails, so does precision. Words stop describing specific stresses, specific mechanisms, and specific adaptations. They become vague stand-ins like “hard,” “a lot,” “fatiguing,” or “intense.” Labels that feel descriptive but actually say very little about what is happening physiologically.

3-4 Inches versus “a little bit.” INOL 2.5 versus “a hard workout.” These are not semantic preferences. They are fundamentally different levels of instructional clarity. The more imprecise the language, the less control we have over the stimulus, the outcome, and the adaptation we claim to be creating.

Recruitment will serve as a clear example of this breakdown because it exposes what happens when vague language is allowed to masquerade as explanation. The same failure of precision appears everywhere once you start looking for it.

Recruitment as an Example of Language Failure

When coaches say “recruitment,” they are rarely referring to the same thing.

In practice, the term is used to describe a wide range of phenomena, including general muscle activation, perceived effort or neural drive, high EMG amplitude, mind muscle connection, high-threshold motor unit involvement, Type II fiber contribution, or full motor unit pool recruitment.

These concepts are related, but they are not interchangeable. More importantly, they are not equally relevant for every training adaptation. The issue is not that multiple meanings exist. The issue is that coaches often fail to specify which one they mean, then draw conclusions as if the term carried a single, actionable definition.

This is where language begins to misdirect training decisions.

Recruitment Depends on the Adaptation Being Targeted

Recruitment must always be interpreted relative to the outcome you are trying to produce.

For coordination and stability, the timing and distribution of activation matter. For hypertrophy, the dominant driver is mechanical tension experienced by the muscle fibers (Beardsley, 2017). For maximal strength, the key requirement is sustained high force production by high-threshold motor units under sufficient load.

High activation alone does not guarantee a meaningful strength stimulus. Electromyography reflects neural input to muscle, not mechanical output. EMG can be useful for understanding coordination and stabilization demands, but it cannot be used in isolation to infer force production or long-term strength adaptation (Behm and Anderson, 2004; Behm, 2012).

A muscle can be highly active while producing relatively little external force.

Recruitment Without Load Is Not a Strength Stimulus

High-threshold motor units can be recruited through heavy loading, fatigue, or high-velocity contractions. Recruitment alone, however, is not sufficient for adaptation. The recruited fibers must experience high mechanical tension for a sufficient duration to drive strength gains (Beardsley, 2017).

A maximal vertical jump recruits a large portion of the motor unit pool, yet produces minimal hypertrophy and modest maximal strength gains because the duration of high tension is extremely brief. A heavy squat also recruits high-threshold motor units, but keeps them under load across multiple seconds and repetitions.

The difference is not recruitment.

The difference is mechanical tension over time.

This distinction matters because vague language often collapses these differences into a single explanation.

Where Language Breaks Down in the Unilateral vs Bilateral Debate

Unilateral exercises are frequently praised for producing high muscle activation. EMG readings are elevated, stabilizers are heavily involved, and perceived effort is high. From this, it is often concluded that unilateral exercises “recruit more muscle” and are therefore superior for strength development.

This conclusion confuses activation with force production.

Strength adaptations are driven by exposure to high force demands, not by discomfort, complexity, or perceived effort.

Bilateral lifts allow substantially greater external loading, resulting in higher mechanical tension across the musculoskeletal system. This ability to load heavily is a primary reason bilateral training is consistently associated with superior improvements in maximal strength and power (Zhang et al., 2023).

In contrast, maximal unilateral lifts are commonly limited by balance, posture, or joint control rather than exhaustion of the prime movers. Neural drive is high, but it is distributed across stabilization demands rather than concentrated on producing force.

Research on unstable resistance training shows that force output decreases substantially under unstable conditions even when muscle activation remains high (Behm and Anderson, 2004; Behm, 2012). Muscles are working hard, but much of that work is spent maintaining position rather than moving load.

High activation does not equal high force.

Different Tools, Different Outcomes

Neural adaptations are task-specific. Bilateral lifts concentrate neural output toward producing force against an external load. Unilateral lifts distribute neural output across force production, balance, and posture.

This makes unilateral training valuable for coordination and control, but less efficient for maximizing absolute force production.

Meta-analytic evidence reflects this specificity. Bilateral training is more effective for improving bilateral strength and power, while unilateral training shows greater transfer to unilateral performance tasks (Zhang et al., 2023).

This is not a question of superiority. It is a question of precision.

Bilateral lifts raise the ceiling of force production.

Unilateral lifts refine how that force is expressed.

If the ceiling never rises, refinement eventually plateaus.

Why This Matters Beyond Recruitment

Recruitment is not unique. It is simply one of the clearest examples of what happens when vague language replaces specificity.

The same failure appears when coaches say an athlete did “a lot of volume,” was “fatigued,” or completed a “hard workout” without defining load, duration, density, or proximity to failure. These words feel explanatory, but they offer little control over the stimulus or the outcome.

Training does not adapt to adjectives. It adapts to specific, measurable stress.

Conclusion: Precision in Language Enables Precision in Training

Recruitment is not a single variable. Without clarification, it obscures more than it explains. High activation does not guarantee high force. Effort does not equal intensity in a strength context. EMG does not predict adaptation on its own.

Misunderstood language is one of the most common sources of disagreement in strength training because once words lose precision, the physiology is inevitably misunderstood.

When coaches specify what they mean, confusion dissolves. Training decisions become clearer. Programs become more repeatable. Outcomes become easier to evaluate.

Language should not be a shield that coaches can hide behind. Training is judged by adaptation, not by intention or description. Precision is not pedantic. It is what allows a coach to define, repeat, and evaluate a stimulus, and it starts with language.

Let’s do a better job with our words. Clear language leads to clear thinking, better programs, and fewer arguments that never needed to happen in the first place.

References

Behm, D. G., and Anderson, K. G. (2004). The role of instability with resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(3), 637 to 640.

Behm, D. G. (2012). The effectiveness of resistance training using unstable surfaces and devices. Sports Medicine, 42(1), 1 to 12.

Beardsley, C. (2017). Mechanical loading and not motor unit recruitment is the key to muscle growth. Strength and Conditioning Research.

Zhang, W., et al. (2023). Effect of unilateral training and bilateral training on physical performance: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 14, 1128250.