Honoring the Beast: How Jordan Feigenbaum’s Classic Nutrition Blog Changed the Way I Build Athletes

Every coach has a few pieces of writing that mark turning points in their career. The first time you read Verkhoshansky, it changes how you see force. The first time you read Bompa, you start thinking in phases. And somewhere along the line, if you were paying attention to strength culture in the last decade, you probably came across Jordan Feigenbaum’s “To Be a Beast.”

When I found that article nearly ten years ago, I was already deep into coaching, surrounded by textbooks, research papers, and a thousand loud opinions about nutrition. Most of what I read back then fell into two camps: either too academic to apply in the real world, or too shallow to trust. Feigenbaum’s piece was different. It was written by someone who’d been under the bar, who spoke the language of training and recovery, and who had the rare ability to connect physiology to practical behavior.

At its core, “To Be a Beast” was simple. Eat with purpose. Use macros as tools. Build meals that support training, recovery, and muscle gain without drifting into obsession or fads. Feigenbaum came from the Starting Strength lineage focused purely on strength and had just moved toward his own lifter-driven model through Barbell Medicine. The blog wasn’t about dogma. It was about systems that actually work.

That message hit home. I decided to test it.

At Yale, and later in the private sector, we began applying the principles with athletes across multiple sports. We weren’t chasing vanity metrics. We wanted to see whether this framework—clear lanes for muscle gain, recomposition, or fat loss—could hold up against the chaos of real life. These weren’t perfect conditions. These were college athletes balancing exams, practices, and late-night team meals.

Within the first month, the results were undeniable. Across roughly seventy players, DEXA scans showed an average of three and a half pounds of new lean tissue while dropping several pounds of fat. They looked different—more defined, sharper lines instead of soft curves—and they performed better. Energy improved. Training quality went up. Recovery was smoother. We repeated it the next year and saw nearly identical results. When we expanded to other teams, the pattern held.

In professional baseball, the results were even more striking. We’ve had starting pitchers log over 150 innings in a season, traveling coast to coast, and still gain six to eight pounds of muscle. No shortcuts. No crash diets. Just structured eating, city by city, guided by the principles that Feigenbaum laid out years ago.

After seeing those results, we decided to apply the same framework to an entirely different demographic—our executive clients. These are thirty- to fifty-year-old professionals, many of whom once had an athletic background decades ago but now find themselves at a training age of zero, caught in the inertia of corporate life. Most of them hadn’t trained seriously in years. They were overworked, under-recovered, and skeptical that such a structured approach to eating would make a meaningful difference.

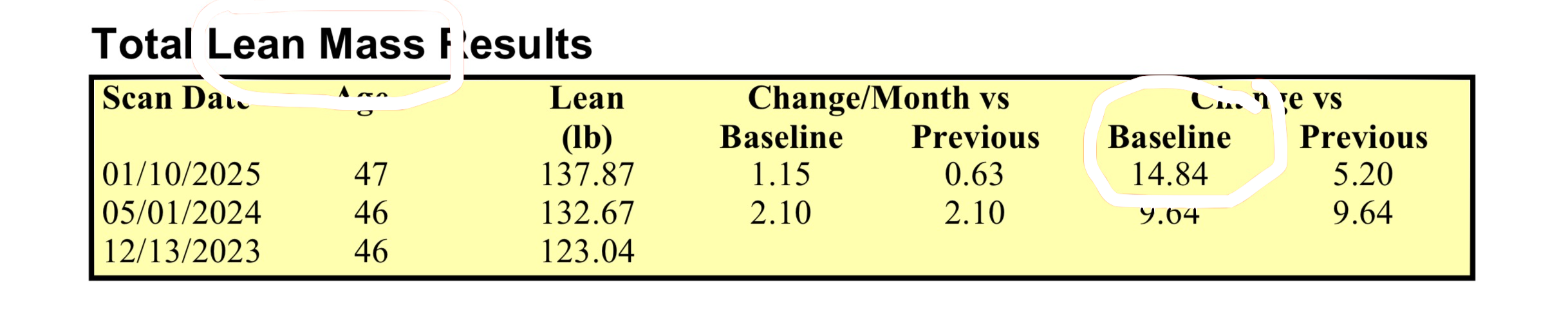

But the results told a different story. After just one year—roughly three to four days a week of structured training—the progress was remarkable. While many saw great success, one executive topped the charts with a fifteen-pound gain in lean tissue in twelve months (see image below). Even more compelling, his VO₂ max improved by nearly eight percent, showing that the new tissue wasn’t just for show—it was functional. It moved the needle in endurance, resilience, and performance under stress. Critics might debate the minutiae, but at some point, the outcomes speak louder than the arguments.

Across every population we’ve tested—from collegiate athletes to professionals to executives—the pattern remains the same. Those who follow the To Be a Beast framework consistently outperform expected norms and the status quo of their sport or demographic. And while I’d like to believe our training systems are world-class, the contrast is clear: those who neglected the nutritional foundation rarely saw the same transformation, regardless of the training plan that was executed.

This style of eating works because it’s both disciplined and forgiving. It gives structure without rigidity. The foundation is protein—a non-negotiable for tissue repair and recovery. Around that, calories and macros are adjusted based on the athlete’s goal. If they’re in a muscle-gain phase, we push fuel strategically. If they’re recomposing, we balance intake with output to add lean tissue without adding mass. And if they’re in a fat-loss phase, we focus on protecting muscle while trimming unnecessary weight.

But the real secret is compliance. Most athletes expect to suffer when they “diet.” What surprises them most is how much food they get to eat when it’s structured correctly. They aren’t starving. They’re satisfied, strong, and consistent. That consistency is what drives progress.

In my own coaching, I’ve always believed that the best systems are the ones you can repeat under stress. Feigenbaum’s model gave us exactly that—a repeatable, measurable framework that could scale from college rosters to big-league players. Over time, we built our own Newman HP calculator around it to make implementation seamless. Athletes or coaches can plug in basic data, choose one of the three lanes—gain, recomp, or fat loss—and immediately see the macro and calorie targets. From there, the art begins: adjusting based on DEXA scans, training data, and readiness scores.

None of this replaces the expertise of dietitians or the nuance of individual needs. But it gives coaches a shared language with the nutrition staff and, more importantly, gives athletes confidence. When an athlete knows the plan, understands the why behind it, and feels the difference in their performance, they stop guessing. That sense of control is powerful.

Feigenbaum wrote his piece in an era when strength culture was still fighting the myths of clean eating, extreme bulking, and endless cardio. What made “To Be a Beast” endure is its humility. It doesn’t promise miracles. It promises a process—a way to eat like training matters.

A decade later, that idea still holds up. At Newman HP, we’ve seen it turn into muscle on the scale, power on the field, and confidence in the mirror. The data speaks for itself. The athletes feel it. And for every young coach looking to bridge science and practice, Feigenbaum’s message remains a compass point.

We didn’t invent this framework—we refined it, measured it, and carried it forward. The credit belongs to Jordan Feigenbaum, whose writing gave strength coaches something they’d been missing for years—a place to start. Nutrition wasn’t the enemy; it was just the elephant in the room. Most coaches either avoided it entirely, deferring to a nutritionist, or went all-in on something so extreme that it couldn’t last beyond a few weeks. To Be a Beast struck the balance. It was the first plan that every coach could look at, nod, and say, “Yeah… that makes sense.”

If there’s one takeaway, it’s this: you don’t need a new trend. You need a system that respects physiology, honors the work, and lasts. To Be a Beast did exactly that. It changed the way we feed athletes—and, in its own quiet way, the way we coach them. Our hope is that it does the same for you. Share it with your athletes, your staff, or anyone who’s lost in the noise of modern nutrition. If it can help them see food not as a complication but as a competitive advantage, then it’s done its job. We’ve seen it transform how our athletes look, feel, and perform—and we believe it can do the same in every weight room, boardroom, and locker room that’s ready to take the next step.

Resources & Links

Original Inspiration:

Jordan Feigenbaum, “To Be a Beast” – Barbell Medicine

Explore the Framework:

To Be A Beast Calculator— Click Here

Further Reading:

Kraemer, W. J., & Ratamess, N. A. – Developing the Athlete

Zatsiorsky, V. M. – Science and Practice of Strength Training